As I kick off into the new year, I’ve been thinking about a panel discussion we hosted recently at Downtown Orlando UX with our friends from ProductTank Orlando. The conversation was a deep dive into how AI is redefining product and user experience roles and had an energy that made me optimistic about where our industry is headed. The consensus among our four amazing panelists was that while AI is a powerful thought partner, it’s just another tool that augments our existing skills rather than serving as a replacement for professional expertise. Elliott Politte, UX Principal at The Home Depot mentioned that, “the actual craft of pushing pixels is changing, but the way we solve the problems and how we collaborate and make things human isn’t.”

Kim Morrow, Head of UX at Alegeus and UX Professor at Full Sail University echoed this sentiment in what was my favorite quote of the evening:

“Figma does not make a designer. Word does not make a writer. A hammer does not make a carpenter, and AI doesn’t make anybody anything.”

The panel also explored how AI is blurring the lines between disciplines and turning us into generalists who must lean into tasks that would normally be outside our wheelhouse to stay competitive. Here’s the full recording if you’d like to check it out (panelists start at ~6:45):

While I enjoy exploring new ways to integrate AI into my own work and leveraging agentic workflows to make software more delightful, optimism without a healthy dose of skepticism is just hype. I’m equally interested in understanding AI’s task-specific viability and whether these tools actually help us craft software that’s better for humans, or if they’re simply aiming to replace humans altogether.

My friend and former colleague Gregg Bernstein explored those topics last month in a lightning-rod of a post titled “The only winning move is not to play.” Gregg argues that when user researchers offload core parts of their craft to generative AI, they debase their own expertise and make themselves interchangeable with the tools marketed to replace them. It’s a thought-provoking read that wraps up with the question, “What is your red line?

“My red line is trading in the parts of the job I am both an expert in and enjoy for tasks that make the job something else entirely.” – Gregg Bernstein

The thread I see through both the stories of our industry panelists and Gregg’s post is that for all of us working in tech, the job is becoming something else entirely. It doesn’t matter if you’re a researcher, product manager, designer, or engineer – the hard-earned skills that define our professional value continue being delegated to, or at least augmented by AI.

Call me a masochist, but I once enjoyed and was an expert in slicing up Photoshop comps and hand-coding them into complex, table-based website layouts. Learning to design with CSS and semantic markup, especially during the dawn of the web standards movement when cross-browser support was so wildly inconsistent, wasn’t just a minor pivot. Web designers had to throw out everything they knew about translating pixels to code. In many ways, it feels like we’re in the midst of the “Browser Wars” era of AI development. Periods of technological transformation like this (and we’ve experiences many over the course of web history) are never easy. They require us to learn, experiment, and adapt. The unique skills we pick up along the way don’t disappear though. Just as my ancient table-coding knowledge still comes in handy occasionally when updating HTML email templates, our specialized skills and subject-matter expertise remain valuable as we grow.

As helpful as AI tools already are, they’re also as slow, incompetent, and inaccurate as they’ll ever be. The designers who stayed in the web industry through the CSS revolution weren’t the ones who clung to table layouts and spacer GIFs. They were the tinkerers who created CSS Zen Garden entries, who read every A List Apart post, who experimented with the latest CSS developments, and carried what they knew into the next chapter. To stay relevant in the age of AI, we have to maintain a sense of wonder, continuing to push into the unknown and uncomfortable.

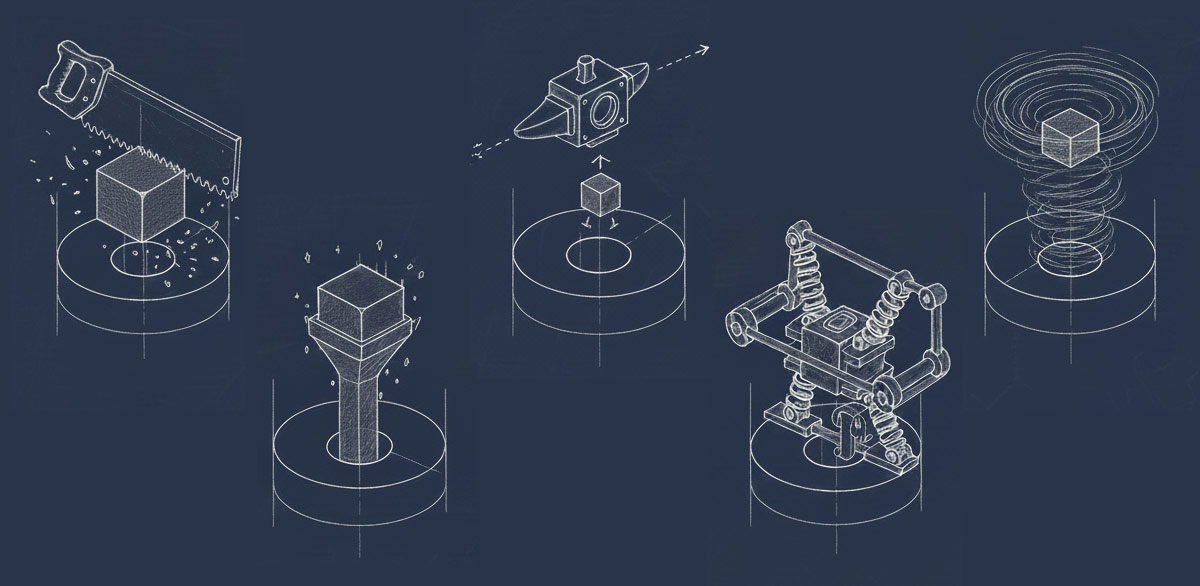

I respect Gregg’s position, and think we all need to have our red lines, but I’d draw mine a little differently. His is refusing to use AI for the core research tasks that define his role. I get it, and there’s integrity in that position. I worry that holding certain tasks sacred though, puts us in the same position as the web designers who continued to build with tables or Flash until those practices became obsolete. The biggest risk isn’t in exploring these tools, it’s in refusing to at least try to test out their value. AI is blurring the lines between our disciplines whether we like it or not, requiring more from all of us and making everyone a deeper generalist. Or, as Jared Spool calls them, “broken comb shaped” individuals. That curiosity, and openness to experimenting with AI tools will determine whether we’re going to help shape what comes next or let the industry evolve around us.

My red line isn’t about the work I refuse to let AI take from my hands; It’s about refusing to let AI tools replace my judgment. It’s up to each of us to ensure quality, maintain user empathy, and apply critical thinking to the experiences we’re creating with these tools. I want to know, and will continue to explore, which tedious tasks (especially those I’m an expert in) can be sped up or eliminated so I can focus on work that requires my perspective or helps me expand my own craft.

Perhaps most importantly, I want to continue modeling curiosity and sharing what I’m learning along the way with the next generation of UX professionals, because they’re inheriting a software industry that’s already changed. So yeah, stay curious, friends. Experiment and discover where these things fail spectacularly. Figure out for yourself what AI workflows give you a power up and which ones are just wasting time and turns. Think about where your red line is and what uniquely human value you bring to the table. The UX field will continue evolving in 2026. The professionals who thrive won’t be the ones who adopt every AI tool, and they won’t be the ones who refuse to engage at all. It’ll be the individuals who tinker and continually deepen their expertise that will shape what comes next.